Larson Cartoon Okay Lets Try This Again Trying to Hang a Man but Hung the Horse Image

Example of a modern cartoon. The text was excerpted by cartoonist Greg Williams from the Wikipedia commodity on Dr. Seuss.

A cartoon is a blazon of illustration that is typically drawn, sometimes animated, in an unrealistic or semi-realistic style. The specific pregnant has evolved over time, merely the modern usage ordinarily refers to either: an epitome or series of images intended for satire, caricature, or sense of humour; or a motion movie that relies on a sequence of illustrations for its blitheness. Someone who creates cartoons in the first sense is called a cartoonist,[i] and in the second sense they are usually called an animator.

The concept originated in the Middle Ages, and first described a preparatory cartoon for a piece of art, such as a painting, fresco, tapestry, or stained drinking glass window. In the 19th century, outset in Punch mag in 1843, cartoon came to refer – ironically at first – to humorous illustrations in magazines and newspapers. Then it likewise was used for political cartoons and comic strips. When the medium developed, in the early 20th century, information technology began to refer to blithe films which resembled print cartoons.[ii]

Fine fine art

Christ's Charge to Peter, one of the Raphael Cartoons, c. 1516, a total-size cartoon design for a tapestry

A cartoon (from Italian: cartone and Dutch: karton—words describing stiff, heavy paper or pasteboard) is a full-size drawing made on sturdy newspaper as a pattern or modello for a painting, stained glass, or tapestry. Cartoons were typically used in the production of frescoes, to accurately link the component parts of the composition when painted on damp plaster over a series of days (giornate).[3] In media such every bit stained tapestry or stained drinking glass, the cartoon was handed over by the artist to the skilled craftsmen who produced the concluding work.

Such cartoons often have pinpricks along the outlines of the pattern so that a purse of soot patted or "pounced" over a drawing, held against the wall, would exit black dots on the plaster ("pouncing"). Cartoons by painters, such every bit the Raphael Cartoons in London, and examples by Leonardo da Vinci, are highly prized in their ain right. Tapestry cartoons, usually colored, were followed with the middle by the weavers on the loom.[2] [4]

Mass media

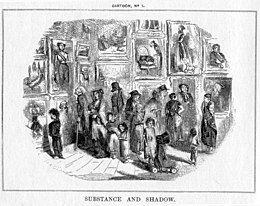

John Leech, Substance and Shadow (1843), published as Cartoon, No. i in Punch, the first use of the word cartoon to refer to a satirical drawing

In print media, a cartoon is an analogy or serial of illustrations, usually humorous in intent. This usage dates from 1843, when Punch magazine applied the term to satirical drawings in its pages,[5] particularly sketches by John Leech.[6] The offset of these parodied the preparatory cartoons for k historical frescoes in the and then-new Palace of Westminster. The original title for these drawings was Mr Punch'southward face is the letter Q and the new title "cartoon" was intended to be ironic, a reference to the self-aggrandizing posturing of Westminster politicians.

Cartoons can exist divided into gag cartoons, which include editorial cartoons, and comic strips.

Modern unmarried-console gag cartoons, establish in magazines, generally consist of a unmarried drawing with a typeset caption positioned beneath, or—less often—a speech balloon.[vii] Newspaper syndicates have as well distributed single-panel gag cartoons by Mel Calman, Bill Holman, Gary Larson, George Lichty, Fred Neher and others. Many consider New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno the begetter of the modernistic gag cartoon (equally did Arno himself).[8] The roster of mag gag cartoonists includes Charles Addams, Charles Barsotti, and Chon Day.

Pecker Hoest, Jerry Marcus, and Virgil Partch began as magazine gag cartoonists and moved to syndicated comic strips. Richard Thompson illustrated numerous feature articles in The Washington Postal service before creating his Cul de Sac comic strip. The sports department of newspapers usually featured cartoons, sometimes including syndicated features such equally Chester "Chet" Brown's All in Sport.

Editorial cartoons are constitute almost exclusively in news publications and news websites. Although they also employ humor, they are more serious in tone, normally using irony or satire. The art usually acts as a visual metaphor to illustrate a betoken of view on electric current social or political topics. Editorial cartoons often include speech balloons and sometimes use multiple panels. Editorial cartoonists of note include Herblock, David Depression, Jeff MacNelly, Mike Peters, and Gerald Scarfe.[ii]

Comic strips, as well known equally drawing strips in the United Kingdom, are found daily in newspapers worldwide, and are usually a short series of cartoon illustrations in sequence. In the Usa, they are not commonly called "cartoons" themselves, only rather "comics" or "funnies". Nonetheless, the creators of comic strips—as well as comic books and graphic novels—are usually referred to every bit "cartoonists". Although humor is the virtually prevalent subject affair, adventure and drama are also represented in this medium. Some noteworthy cartoonists of humorous comic strips are Scott Adams, Charles Schulz, E. C. Segar, Mort Walker and Bill Watterson.[2]

Political

Political cartoons are like illustrated editorial that serve visual commentaries on political events. They offer subtle criticism which are cleverly quoted with humour and satire to the extent that the criticized does not become embittered.

The pictorial satire of William Hogarth is regarded as a precursor to the development of political cartoons in 18th century England.[9] George Townshend produced some of the first overtly political cartoons and caricatures in the 1750s.[9] [10] The medium began to develop in the latter role of the 18th century nether the direction of its great exponents, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, both from London. Gillray explored the use of the medium for lampooning and extravaganza, and has been referred to as the begetter of the political cartoon.[xi] Past calling the king, prime ministers and generals to account for their behaviour, many of Gillray'southward satires were directed against George III, depicting him as a pretentious buffoon, while the bulk of his piece of work was dedicated to ridiculing the ambitions of revolutionary France and Napoleon.[11] George Cruikshank became the leading cartoonist in the period post-obit Gillray, from 1815 until the 1840s. His career was renowned for his social caricatures of English life for popular publications.

Nast depicts the Tweed Ring: "Who stole the people'due south money?" / "'Twas him."

By the mid 19th century, major political newspapers in many other countries featured cartoons commenting on the politics of the solar day. Thomas Nast, in New York City, showed how realistic High german drawing techniques could redefine American cartooning.[12] His 160 cartoons relentlessly pursued the criminal characteristic of the Tweed machine in New York Metropolis, and helped bring it down. Indeed, Tweed was arrested in Espana when police identified him from Nast's cartoons.[13] In Britain, Sir John Tenniel was the toast of London.[xiv] In France nether the July Monarchy, Honoré Daumier took up the new genre of political and social extravaganza, most famously lampooning the rotund Male monarch Louis Philippe.

Political cartoons can exist humorous or satirical, sometimes with piercing effect. The target of the sense of humor may complain, but tin can seldom fight dorsum. Lawsuits have been very rare; the first successful lawsuit against a cartoonist in over a century in Britain came in 1921, when J. H. Thomas, the leader of the National Matrimony of Railwaymen (NUR), initiated libel proceedings against the magazine of the British Communist Political party. Thomas claimed defamation in the form of cartoons and words depicting the events of "Blackness Friday", when he allegedly betrayed the locked-out Miners' Federation. To Thomas, the framing of his image by the far left threatened to grievously degrade his character in the popular imagination. Soviet-inspired communism was a new element in European politics, and cartoonists unrestrained past tradition tested the boundaries of libel police. Thomas won the lawsuit and restored his reputation.[15]

Scientific

Cartoons such as xkcd have as well constitute their place in the world of science, mathematics, and technology. For example, the cartoon Wonderlab looked at daily life in the chemical science lab. In the U.Southward., i well-known cartoonist for these fields is Sidney Harris. Many of Gary Larson's cartoons have a scientific flavor.

Comic books

Books with cartoons are normally mag-format "comic books," or occasionally reprints of newspaper cartoons.

In Britain in the 1930s adventure magazines became quite popular, especially those published by DC Thomson; the publisher sent observers around the country to talk to boys and acquire what they wanted to read about. The story line in magazines, comic books and cinema that most appealed to boys was the glamorous heroism of British soldiers fighting wars that were exciting and just.[16] D.C. Thomson issued the outset The Not bad Comic in Dec 1937. It had a revolutionary design that bankrupt abroad from the usual children's comics that were published broadsheet in size and not very colourful. Thomson capitalized on its success with a like production The Beano in 1938.[17]

On some occasions, new gag cartoons have been created for book publication, as was the case with Think Small, a 1967 promotional volume distributed as a giveaway by Volkswagen dealers. Neb Hoest and other cartoonists of that decade drew cartoons showing Volkswagens, and these were published forth with humorous automotive essays by such humorists as H. Allen Smith, Roger Price and Jean Shepherd. The volume's pattern juxtaposed each drawing aslope a photograph of the cartoon's creator.

Blitheness

Because of the stylistic similarities between comic strips and early animated films, drawing came to refer to animation, and the word drawing is currently used in reference to both blithe cartoons and gag cartoons.[18] While blitheness designates any way of illustrated images seen in rapid succession to give the impression of movement, the word "drawing" is well-nigh ofttimes used as a descriptor for television programs and short films aimed at children, mayhap featuring anthropomorphized animals,[19] superheroes, the adventures of kid protagonists or related themes.

In the 1980s, drawing was shortened to toon, referring to characters in animated productions. This term was popularized in 1988 by the combined live-action/blithe flick Who Framed Roger Rabbit, followed in 1990 past the blithe TV series Tiny Toon Adventures.

Meet too

- Billy Republic of ireland Drawing Library & Museum

- Extravaganza

- Comics

- Comics studies

- Histoire de M. Vieux Bois

- List of comic strips

- Listing of cartoonists

- List of editorial cartoonists

- Teen sense of humor comics

References

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Lexicon.

- ^ a b c d Becker 1959

- ^ Constable 1954, p. 115.

- ^ Adelson 1994, p. 330.

- ^ Dial.co.u.k.. "History of the Cartoon". Archived from the original on 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2007-11-01 .

- ^ Adler & Hill 2008, p. thirty.

- ^ Bishop 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Maslin, Michael (May 5, 2016). "The Peter Arno Cartoons That Help Rescue The New Yorker". The New Yorker . Retrieved 2018-09-xvi .

- ^ a b Printing 1981, p. 34.

- ^ Chris Upton. "Birth of England's pocket cartoon". The Gratuitous Library.

- ^ a b Rowson 2015.

- ^ Adler & Hill 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Adler & Hill 2008, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Morris & Tenniel 2005, p. 344.

- ^ Samuel S. Hyde, "'Please, Sir, he called me "Jimmy!' Political Cartooning before the Law: 'Black Friday,' J.H. Thomas, and the Communist Libel Trial of 1921," Contemporary British History (2011) 25#iv pp 521-550

- ^ Ernest Sackville Turner, Boys Will Exist Boys: The Story of Sweeney Todd, Deadwood Dick, Sexton Blake, Baton Bunter, Dick Barton et al. (3rd ed. 1975).

- ^ M. Keith Booker (2014). Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas [4 volumes]: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. p. 74. ISBN9780313397516.

- ^ Walasek 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Wells 2008, p. 41.

Bibliography

- Adelson, Candace (1994). European tapestry in the Minneapolis Found of Arts. Minnesota: Minneapolis Institute of Arts. ISBN9780810932623.

- Adler, John; Hill, Draper (2008). Doomed by Cartoon: How Cartoonist Thomas Nast and the New York Times Brought Down Boss Tweed and His Ring of Thieves. Morgan James Publishing. ISBN978-ane-60037-443-2.

- Becker, Stephen D.; Goldberg, Rube (1959). Comic Fine art in America: A Social History of the Funnies, the Political Cartoons, Magazine Humor, Sporting Cartoons, and Blithe Cartoons. Simon & Schuster.

- Bishop, Franklin (2009). Cartoonist's Bible: An Essential Reference for Practicing Creative person. London: Chartwell Books. ISBN978-0-7858-2085-vii.

- Blackbeard, Bill, ed. (1977). The Smithsonian Drove of Newspaper Comics. Smithsonian Inst. Press.

- Constable, William George (1954). The Painter's Workshop. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN9780486238364 . Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- Horn, Maurice (1976). The World Encyclopedia of Comics . Chelsea Business firm.

- Morris, Frankie; Tenniel, Sir John (2005). Artist Of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, And Illustrations Of Tenniel. University of Virginia Press. ISBN9780813923437.

- Press, Charles (1981). The Political Drawing. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN9780838619018.

- Robinson, Jerry (1974). The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art. G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Rowson, Martin (21 March 2015). "Satire, sewers and statesmen: why James Gillray was king of the cartoon". The Guardian.

- Walasek, Helen (2009). The Best of Punch Cartoons: two,000 Humor Classics. England: Overlook Press. ISBN978-ane-5902-0308-eight.

- Wells, Paul (November 28, 2008). The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Civilization. Rutgers University Press. ISBN978-0-8135-4643-8.

- Yockey, Steve (2008). Cartoon. Samuel French. ISBN978-0-573-66383-3.

External links

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cartoons. |

| | Look up cartoon in Wiktionary, the free lexicon. |

- Dan Becker, History of Cartoons

- Marchand collection cartoons and photos

- Stamp Human action 1765 with British and American cartoons

- Harper'southward Weekly 150 cartoons on elections 1860–1912; Reconstruction topics; Chinese exclusion; plus American Political Prints from the Library of Congress, 1766–1876

- "Graphic Witness" political caricatures in history

- Keppler cartoons

- current editorial cartoons

- Alphabetize of cartoonists in the Fred Waring Collection

- International Guild for Sense of humor Studies

- Fiore, R. (2010-01-31). "Adventures in Nomenclature: Literal, Liberal and Freestyle". The Comics Periodical. Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2013-02-05 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cartoon

0 Response to "Larson Cartoon Okay Lets Try This Again Trying to Hang a Man but Hung the Horse Image"

Post a Comment